Marking and written feedback in science

Feedback sits at the top of Professor John Hattie’s table of effect sizes on education performance. Written feedback is an important part of the overall feedback machine and gives teachers a unique opportunity for a 1-1 with students, allowing feedback to take place in both directions. That’s not to say though that all feedback is good – in a meta-analysis Kluger and DeNisi (1996) showed that just over 1/3rd of feedback interventions decreased performance!

Writing detailed feedback on individual pieces of work is incredibly time consuming. Often, the pressure to get the marking done means we have to resort to generic comments or easy to set targets such as ‘use more key words in your answer’. A more sustainable approach is to capture common errors and mistakes during rapid marking (possibly by annotating a blank version of the task with common class errors) and then use this information to perform a whole class re-teach at the start of the next lesson. Reassuringly, most students will have the same misconceptions and make the same errors so don’t feel guilty with this whole class approach!

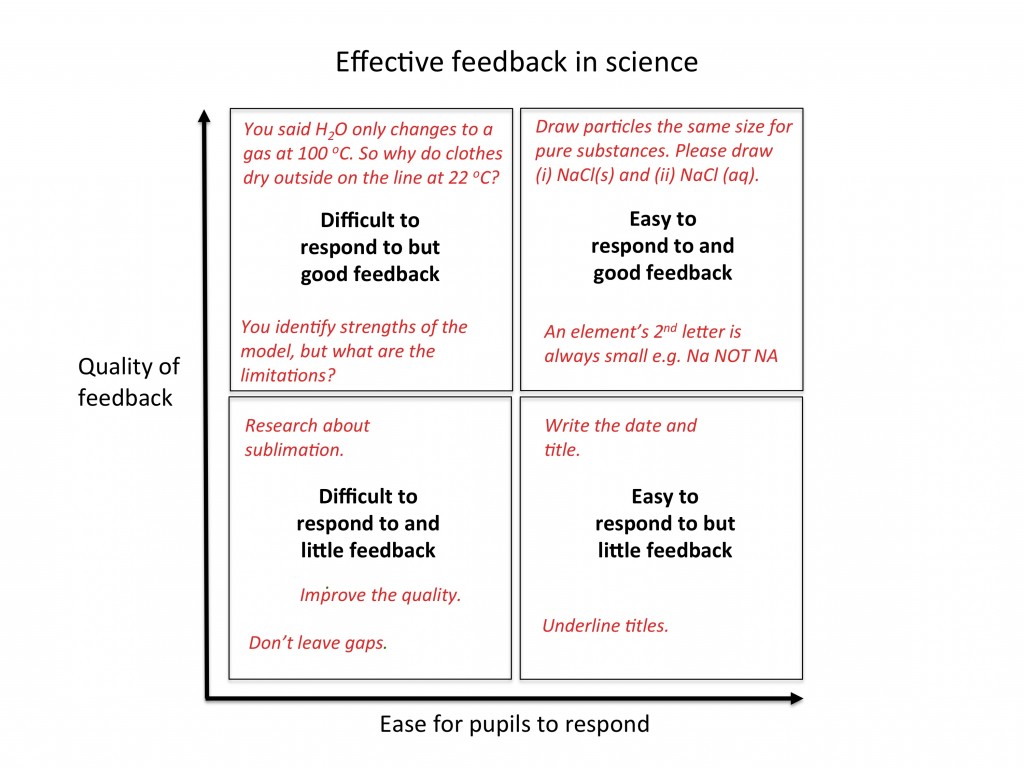

If you have time to write feedback, then I hope the below will help. Some ideas have been taken and adapted from Black and Wiliam (1998).

Please download the blank quadrants to use in your own training sessions on written feedback.

Do make sure:

- you set tasks that are sufficiently diagnostic to facilitate useful feedback from an expert

- feedback is phrased in a way that students can understand and is relevant to future work. We want to improve the student.

- pupils are trained in how to respond to the feedback and this is routinised

- the feedback between pupils and a teacher is thoughtful, reflective and focused to evoke and explore understanding of key concepts

- each student is given the opportunity and help to work at improvements in class and that the teacher has time to review this in the lesson

- you write feedback near where the error occurs in the text

- you annotate a blank copy of the task with common errors/misconceptions as you mark to inform whole class feedback in the next lesson.

Don’t:

- write standalone ‘stretch’ questions that don’t refer to the work just marked

- give overly specific feedback that only relates to that piece of work – pick out the feedback that is going to enable success in future work. For example, it’s probably more important students can balance equations than state the conditions for rusting.

- make comparisons with other pupils

- comment overly on quantity and presentation; learning is the important bit!

- overemphasise grades and marks

- get into lengthly written dialogues with students

- give personal feedback.

Further reading

- Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Granada Learning.

- Elliott, Victoria, et al. (2016). A marked improvement? A report from the Education Endowment Foundation.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological bulletin, 119(2), 254.

- Wiliam, D. (2016) Mr Barton Maths Pod Cast