Standarisation of marking

I recently saw some fascinating data. Students from different schools sat two identical tests, let’s call these tests A and B. Test A was marked by a human and test B was marked by a computer. Performance in each test was then correlated i.e. did test A and B rank students in the same order? The answer was, as is so often the case in education, it depends. For some schools, the correlation between the two tests was high i.e. both tests ordered the students in the same way. For other schools the correlation was low i.e. the tests ranked students in different ways. Now, there’s a few reasons for why this could be, but I want to explore one possible cause: consistency of marking. Often we are so focussed on creating valid and reliable assessments that we don’t give enough thought to the conditions of the assessment or how it is marked. But marking is hard, and we all need support and training on how to mark better.

So how can we improve our ability to mark a test? Below is a standardisation protocol that works well and can be used in any school or department meeting to help make judgements more accurate and consistent. As well as helping mark better, this is also a powerful professional development opportunity because it opens up dialogue about what great student work looks like.

Start with making a dummy paper and a marking commentary

The process starts with an ‘expert’ writing a dummy paper. This is essentially answering the test that students sat with mocked up answers. The best dummy papers are written in such a way that they represent common student answers, misconceptions and errors as well as modelling some exemplary student responses. It’s a good idea to have the exam board marking guidance with you when you write the dummy paper so you can make some deliberate mistakes such as:

- phonetic spelling e.g fizzics

- formulas instead of names e.g. HCl not hydrochloric acid

- marking of lists e.g. cats have four legs and dogs have three legs scores 0

- crossed out answers that are not replaced are still marked

- using ‘it’ without referring to what ‘it’ is e.g. it has chlorophyll may score 0

- penalising an error only once e.g. 1 sheep + 3 sheep = 5 sheep (wrong); 5 sheep have 20 legs (right) so one of two marks awarded

Alongside creating your dummy paper, it’s a good idea to create a marking commentary. This is the expert’s view of how many marks each question is worth and the rationale as to why marks are, or are not awarded. Click here for an example of a marking commentary.

First teachers mark – what do YOU think?

Once students have sat the actual test, but before marking has begun, arrange a time to get the department together. Hand out your dummy paper along with a mark scheme and Post-it and ask teachers to mark the paper in silence – exam conditions!

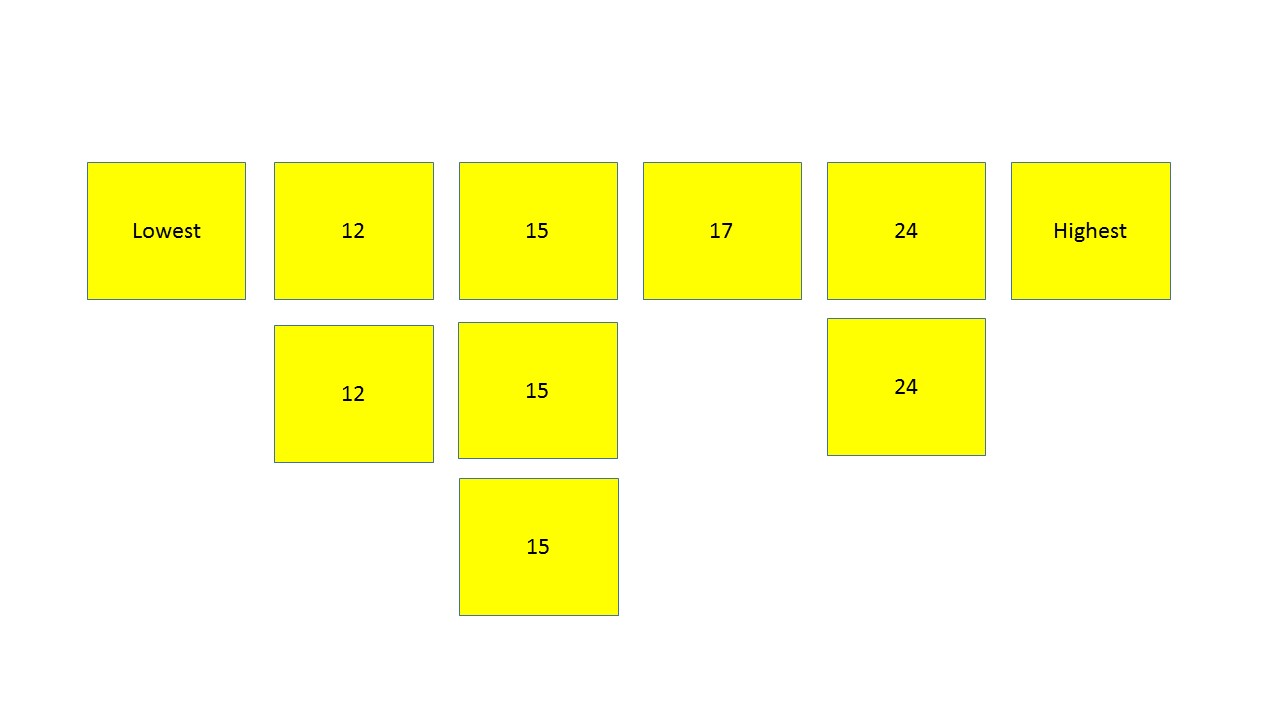

It’s important you don’t allow teachers to discuss at this stage. This can be a scary exercise so create a supportive atmosphere. However, it’s crucial that each teacher assigns a mark to the paper. Once the paper has been marked, ask teachers to write just the total mark on a Post-it. Now collect in the Post-its and arrange these anonymously on the board in order of increasing marks.

The great debate – discussing marks awarded and agreeing a consensus

Hopefully, you will have now exposed a mark range. This makes the point that marking is hard and so standardisation is necessary. Teachers are often amazed, even in subjects such as science and maths, at how awarded marks for the same answers can differ. Now working in groups of three on separate tables, teachers should reach a consensus mark for the paper. Groups should spend time reviewing each question together, debate why they awarded each mark and then come up with an agreed ‘table mark’. It can be helpful here to provide an additional copy of the dummy paper along with general exam board guidance on marking.

The big reveal – do we agree with the expert?

Each table now shares their agreed mark with the wider department. You could write these group marks on the board. Now hand out the marking commentary on a piece of paper to each person. This is the expert view that lists the marks awarded for each question and the all important explanation. Give time for some silent reflection before opening up the table discussions. Stand back and watch the debate flare as the expert gets some ‘feedback’!

Reflection and resolution

Once teachers have had a chance to review the expert’s marking commentary, you can then take feedback to agree the final, group consensus. Undoubtedly the expert will have made some of their own judgement errors. This can be a tricky conversation to manage, so you may prefer groups to simply edit the marking commentary and hand this back in. What is important is that you allow groups and individuals time to reflect on their own marking, where were they generous and why? What new knowledge did they get about awarding marks? How has their own subject knowledge developed? Encourage teachers to think about how this new knowledge is going to ensure consistency when they mark their own papers. If there is time you can then repeat the process with another piece of student work.

So why is this a powerful standardisation approach?

I think the reason this process works is because it gives teachers feedback on their own marking and provides a strong case for why standardisation is important. Secondly, it encourages a professional dialogue between colleagues around student work, subject knowledge and mark schemes – with lots of opportunity for discussion and construction. Thirdly, this can be quite a fun and motivating exercise – you want to find out if the mark you awarded is ‘right’.

A final word of warning. There can be an incredibly passionate debate about what marks are and are not awarded. If not managed carefully, debate can snowball out of control! The key is to structure the session so that differences in opinion can be captured in tables and not managed as a whole group.

At the end of the day mark schemes are judgement calls. The consensus is not a truth, it’s just an attempt to help teachers mark more fairly so that students are all given an equal opportunity to succeed.

Leave a Reply