Deep learning in science and making meaning

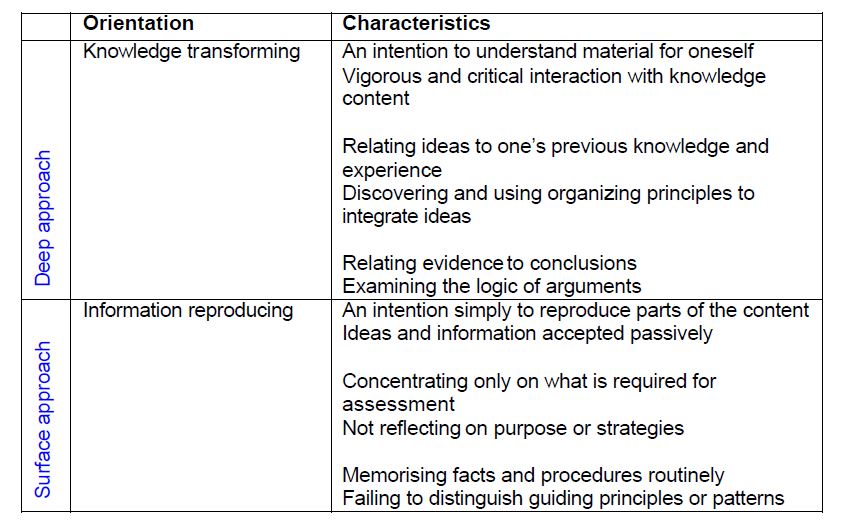

Students can approach any task from either a learning approach focused on understanding the material, or a learning approach focused on reproducing it. These two learning approaches were termed deep learning and surface learning respectively (Marton and Saljo, 1976). The University of Oxford have published an excellent essay summarising these two approaches to learning. I have summarised some of the best bits below. We want out students to make meaning and learn deeply because information is more likely to be remembered.

Misunderstandings of deep learning

It is often assumed that deep learning involves discovery based, constructivist behaviours whilst surface learning involves learning lots of facts. This incorrect interpretation fails to take into account that deep learning also requires students to learn lots of facts, the difference is that deep learning requires the students to then make meaning from what they have learnt. Meaning is made when students are able to connect new ideas to what they already know, and so can use and think about the ideas they are learning about. There is an excellent overview of meaning making by Efraut Furst here. Students are not deep or surface learners, rather they can adopt either of these approaches. Indeed, the learning intention of a student may change as the student progresses through a task e.g. if the work becomes too hard or time is short they may adopt a surface approach.

Why is deep learning better?

I have always been convinced that deep learning results in better learning. Deep learning requires students to make sense of the data, and use this knowledge in different contexts by making links with existing knowledge, integrating ideas and creating novel solutions – this has to be better! Research shows students who are adopting deep approaches tend to have higher quality learning outcomes as they are able to remember the material. Students (and teachers!) may adopt a superficial learning approach in the belief that it is better, but this is often just a pragmatic response to limited time.

How can we encourage deep approaches to learning?

- Clearly state academic expectations [well planned lessons that are objective and not task driven]

- Stimulating teaching – stress your own personal commitment to the subject matter

- Give opportunities for choice in the method and content of study [motivate the students]

- Promote interest in the subject matter and take account of background knowledge [link to prior knowledge]

- Don’t overload the curriculum – prioritise the important bits and remove the noise [link to the Big Ideas of Science]

Further reading

- Marton, F. and Säljö, R., 1976. On Qualitative Differences in Learning: I—Outcome and process*. British journal of educational psychology, 46(1), pp.4-11.